If you think there is something special about a velvet painting — and deep in your heart, you do, even if you say you don’t — try taking in 80 of them at once.

“Black Velvet: A Rasquache Aesthetic,” at Casa de Rosado on Mt. Hope Road, is an exhibit like no other, a furry labyrinth of black velvet and neon colors that feels like 80 cats rubbing against you. Their collective purr is luscious and unnerving.

But the first velvet art exhibit ever mounted in Michigan, according to the curators, is no stunt. That collective purr is a bold assertion of pride in paintings that are usually dismissed as kitschy junk. For the descendants of Mexican immigrants who grew up with velvet paintings, it’s a taste of the past, and a culture that is used to making the best of simple joys.

“Our thing is to make our people proud,” co-curator Elena Herrada said, fighting back tears at the exhibit’s opening Jan. 13. “Pride is shame on its head.”

The paintings mean many things to co-curator and MSU librarian Diana Rivera, who calls it “the art you love to hate.”

“I grew up with them,” Rivera said.

“Nobody calls it art. When you look at the articles and the research, it’s called black velvet painting, almost never art.”

To Rivera’s joy, the show is bringing “salt of the earth folk,” as well as art lovers and students of Chicano culture to Casa de Rosado, the cultural hub journalist Teresa Rosado runs in her century-old home on Lansing’s near southwest side.

On the first Saturday of the exhibit, a couple that was clearly not part of the art cognoscenti came in and kicked the snow off their boots.

“Do you have an angelito?” the man asked.

“No, no angels with halos,” Rivera replied.

“Do you have la Virgencita?” She took him to a painting of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

He put his hand on the painting and bowed his head in prayer.

“I wanted to cry,” Rivera said. “That type of connection is like — yes!”

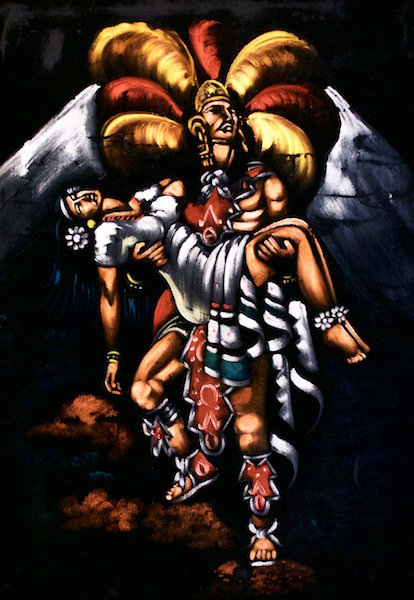

When it came to art in the home, many first-generation Mexican immigrants could only afford 3-for-$15 images of “Ixta and Popo” (Aztec warrior Ixtacihuaátl carrying the princess Popocatépetl), the Virgin of Guadalupe or Mickey Mouse, usually purchased from a truck in a parking lot.

The paintings gave work-weary immigrants marooned in the fronteras norteñas of Michigan a taste of Mexico and the bicultural border towns, now so far away, where the heyday of velvet art began, from the 1940s through the 1980s.

“You’ve seen them at Grandma’s, or your aunt’s house, or maybe you have one,” Rivera said.

Velvet is a soft, generous mother who loves her children equally. At the Lansing exhibit, finely detailed portraits by masters hang alongside anonymous assembly-line work. Jesus Christ, Yosemite Sam, bullfighters and nude women float together comfortably in the midnight medium of velvet.

While gathering paintings for the show, Rivera walked into a Denver shop and asked if they had a velvet painting of Elvis Presley — a “velvis.” The plural is “velvi.” The proprietor rubbed his chin. “Ah, the King, but are you going to have the King of Kings?” he said.

Both kings are represented in the “royalty room,” along with the Duke (John Wayne), the Queen of the Americas (a sobriquet for the Virgin of Guadalupe), and the Queen of Hollywood, Marilyn Monroe.

Liberated from the bullying bromides of Western art criticism, the viewer is free to enjoy whatever pleasures the paintings offer. You can also touch them if you want. “I don’t know if you can really understand it or whether it should be understood,” co-curator Diana Rivera said. “Let’s just appreciate it for what it is.”

“This gives them proper representation, like you would see at the Detroit Institute of Arts or anywhere,” Herrada said. “It actually makes you look at them and understand and describe them, and I’ve never had that experience before.”

Soft-spoken co-curator Minerva

Martinez, who drove from Texas to see the opening, left most of the talking to Rivera and Herrada, but was clearly pleased at the sight of so many velvets in one place.

“To see the end product — it’s just wonderful,” she said.

The idea of a velvet painting exhibit goes back to 2008, when Rivera met Herrada at an MSU Chicano studies class. They talked about the concept of “Rasquache,” which Rivera describes as “kitsch in everyday life.”

“Rasquache” is one of those elusive cultural concepts you can define all day. Cultural critic Tomás Ybarra-Frausto described it as an “underdog perspective” shared by the Mexican poor, and shaped by the experience of Chicanos making sense of life in “Gringolandia.”

Beginning in spring 2017, the curators did their own scrounging, mostly from thrift shops and eBay. As word of the exhibit spread, many closet and attic doors creaked to reveal paintings owners had packed away for years.

As donors warmed to the idea of flipping shame into pride, many of them offered — and some even demanded — that their paintings be included.

“The first step is to admit you have one,” Rivera said with a smile.

The curators consulted two experts along the way: Carl Baldwin from the Velveteria, the Velvet Museum in Los Angeles, and art critic Jennifer Heath, who mounted the first black velvet show in the early 1990s.

The curators asked Baldwin what to do with torn, faded or otherwise imperfect pieces.

“Show them,” Baldwin said. “It shows the persistence of the art.”

Stores stopped carrying velvets years ago, but restaurants were a good source for the curators. Under the cover of a Christmas crowd, Herrada grabbed a pink bullfighter off the wall of Detroit’s Tamaleria Nuevo Leon. She said, “Suzy, do you want this?” to owner Susana Garza-Villerial, and made off with it before she could answer.

The first painting inside the door of Casa de Rosado is a striking portrait of a Tahitian chief with a serious expression and a weathered face, by the father of American velvet paintings, Edgar Leeteg.

Velvet painting goes back to the 1700s, but the American phase began in the 1930s, when Leeteg, a sign painter from Missouri, took a trip to Tahiti and fell in love with the island.

His velvet paintings of Tahitian life, particularly nudes, are the mother lode for historians of velvet painting.

His work quickly found its way to the mainland, helping to spark interest in velvet painting among locals and tourists in Mexican border towns like Juàrez and El Paso. Servicemen returning from duty in the Pacific brought them home, building more interest.

When Georgia businessman Doyle Harden saw velvet paintings sell like mad from parking lot vendors in El Paso and other border towns, and decided to turn velvet into gold.

At the height of the velvet boom in the early 1970s, Harden’s block-long factory in Juárez turned out up to 10,000 paintings a day, using three shifts a day in assembly-line efficiency. Before long, velvets began to appear at Woolworths and Piggly- Wiggly stores.

Rivera bought the show’s main piece, a flamboyant image of Ixta and Popo, at the Frandor Woolworth’s in 1972 on layaway.

“The minimum wage was $1.74,” she said. “I was doing work study and I needed something Chicano for my room.”

Many of the paintings at the Lansing exhibit are unsigned because so many hands worked on them.

“They may seem crude, but one person is painting the sun, another person is painting a cloud, and so on, so they don’t have to switch brushes or paint,” Rivera said.

In the spirit of flipping shame into pride, the exhibit celebrates the sweatshop anonymity of the assembly line, the antithesis of the individualistic Western fetish of the fine artist.

The curators also invited three local artists to paint original works for the exhibit.

Celia Ramirez of Adrian painted a luminous portrait of Frida Kahlo. Judy Trujillo of Pueblo, Colorado, painted a Michigan mashup that packs Wolverine and Spartan insignia, cargo ships, the Supremes and muralist Diego Rivera driving a Ford.

Okemos artist Diego De Leon created a golden, romantic image inspired by “boogie weekends” in his hometown of Los Angles.

“I did it to honor the old days, with the zoot suit riots,” De Leon said. “They still dress like that, the pachucos and pachucas.”

Attempting his first velvet painting gave De Leon a new appreciation of the work all-around him.

“It’s challenging, trying to figure out how many layers you have to put on there to get the bright highlights and colors,” he said. “Velvet absorbs the paint a lot more than canvas. But it also does some of the work for you, with the shadows and depth.”

There’s no hierarchy at the Lansing exhibit. The assembly line paintings hang alongside the new works, finer work by masters like Leeteg, and just plain weird one-offs.

Imperfections and idiosyncrasies are celebrated alongside technical marvels. Rivera and Herrada refer joking but lovingly to the “cross-eyed Jesus,” the “pregnant Jesus” and the Jesus with pink blood.

“You’ll see some bad qualities, but it’s people’s art,” Rivera said. “We’re glad to be able to share it in a space that’s welcoming and inclusive.”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here