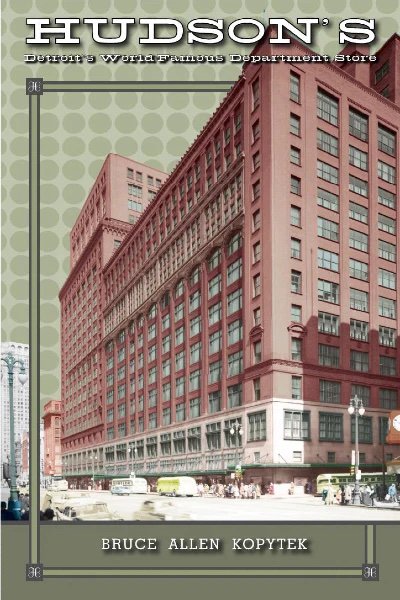

A new, 547-page book on Hudson’s, the venerable downtown Detroit department store, drips with nostalgia. For Detroiters, the store’s name is in league with other iconic brands like Faygo, Vernors, Sanders confections and Better Made.

In “Hudson’s: Detroit’s World-Famous Department Store,” author Bruce Allen Kopytek explains the history of the store and its founder, J.L. Hudson, as well as how “Hudson’s was intertwined with the history of Detroit and its people.”

He describes how in the ‘40s, ‘50s and ‘60s, the store was so ingrained in Southeast Michigan’s shopping experience that the phrase “I got it at Hudson’s” was a cliché that began appearing in the company’s advertising.

He describes how in the ‘40s, ‘50s and ‘60s, the store was so ingrained in Southeast Michigan’s shopping experience that the phrase “I got it at Hudson’s” was a cliché that began appearing in the company’s advertising.

Kopytek, an architect, has a passion for the megalith shopping experience of independent department stores and has written four books on their history. He also maintains a website, thedepartmentstoremuseum.org.

He said when it came to writing this book, “I just couldn’t stop myself.”

When he puts on his architect cap, his passion soars. He certainly makes readers pine for the past as he describes the store’s bank of 51 elevators that guided shoppers to 17 floors where they could buy everything from lawnmowers to designer cocktail dresses. He describes the scene as a “great vista of elevator doors as far as the eye can see.”

In today’s world of strung-out, stand-alone shopping centers, it’s difficult to explain Hudson’s, but if you took a suburban shopping mall and stood it on its end, you still wouldn’t replicate what you could find in the store in its heyday.

Hudson’s boasted 2.1 million square feet, occupying an entire square block on Woodward Avenue in Detroit. Kopytek describes it as “a monstrous brute of a store.” It soared 25 stories, with the top floors used for support staff and operations.

Hudson’s was more than a shopping experience, according to Kopytek: “It was a gathering place for generations of Detroiters.”

In a chapter on special events, he tells how Hudson’s sponsored gatherings that brought shoppers into the store while echoing the company’s desire to be good corporate citizens.

Its creation of the “world’s largest flag” in 1923 is one of the best examples of the company’s corporate largesse. When it first raised the flag, masses of Detroiters gathered to take in the heady experience. It was ultimately replaced and donated to the Smithsonian Institution, which sent it to the American Flag Foundation in Houston, but lack of preservation led to its destruction in 1990.

Kopytek said he was amazed when he discovered the history of the visionary J.L. Hudson, who founded the precursor to what became the world’s third-largest department store in 1881.

“His story is an incredible rags-to-riches tale. He had a ragtag existence pushing a cart. He grew up eating bread without butter but rose to the pinnacle of the department store business,” Kopytek said. “He was also a philanthropist, not only giving his money but his time to the city.”

Kopytek laments, “It’s too bad he didn’t get to see what he created.” Hudson’s would flourish after J.L. Hudson’s death under the leadership of four nephews who took the company in new directions.

As an architect, Kopytek writes eloquently about the corporation’s move to the suburbs — especially its new location at Northland Center in Southfield, which opened in 1954.

“Hudson’s provided the road map for the suburban shopping centers that were soon to come. It was a precursor to the mall. It brought everything under one roof, including the excitement of special events and lots of parking,” he said.

Hudson’s also brought art to its stores. One of its best-known efforts, “Michigan on Canvas,” involved hiring 10 artists to depict the state in 100 paintings. In 1948, the pieces were hung in a gallery at the flagship before touring the state. At the end of the project, the company donated the original art to museums, galleries and libraries.

The cover of the accompanying catalog sold for 75 cents and displayed a portrait of Michigan’s Capitol, executed by Michigan State University art professor John de Martelly.

“Hudson’s always wanted to be the tastemaker,” Kopytek said.

The company’s biggest legacy is arguably the Detroit Thanksgiving Parade, which it founded and sponsored from 1924 to 1979.

In combination with the parade, the store’s 12th floor was turned into a Christmas wonderland and toy shop each year, featuring a merry-go-round, a small Ferris wheel, a “magic forest” and, of course, Santa Claus.

Hudson’s would close its downtown location in 1983, and, after years of rumors that there were plans to save the building, it was imploded in 1998.

“The book is an epitaph — Hudson’s lies in its grave,” Kopytek said.

The first printing of the book is sold out, so it’s worth the effort to reserve a copy either online, at a local bookstore or from the author’s website. Like the store, it has some heft and comes with a $60 price tag.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here