Willie Davis, a Lansing Community College professor, has been running and maintaining the African World Museum and Resource Center since 2000.

“Lansing is a very open city, it allows you to pretty much do what you want to do,” he said.

Through his travels dating back to the 1980s, Davis’s memories of globetrotting fill two small spaces on the Potter-Walsh neighborhood’s Shephard Street with personal photographs, artifacts and few-of-a-kind creations that honor Black history.

Davis is just one of a host of local people who are dedicated to collecting and showcasing Black art in the Lansing area. For underrepresented groups, art can be an act of defiance or a symbol of resistance, demanding to immortalize tradition, technique and oft-overlooked history. Art can also be a symbol of beauty, made with the love and pride of the African Diaspora.

Davis is keenly aware of this beauty, and there isn’t one spot in either building that isn’t adorned with handmade pieces or photographs of the locals he encountered during his travels. He highlights his time in Ghana and Tanzania especially, and the museum honors those countries with handmade masks and unity statues, intricate sculptures made from one piece of wood. A slice of Lansing history is also housed here: Davis was able to acquire the equipment used for the first 24/7, Black-run radio station on Lansing FM cable radio.

Davis isn’t the only independent collector in Lansing. Eugene Cain, a notable educator and photographer, has procured art from Black artists through travel and personal relationships with creators. The home he shares with his wife, Maxine Cain, feels like a museum itself — no art piece is without a story.

“I love creativity,” Eugene Cain said. “Every room in this house is art, anywhere you go.”

Throughout the tour of the main floor, he highlighted artists such as Senegal’s Papissa Diouf; Ghanaian artist Kwesi; and an American artist, Noah Jemison, whom he grew up with in Birmingham, Alabama.

“The first piece I collected from him, I think Noah was in his early 20s. He’s a master artist,” Eugene Cain said.

In the 1980s, he commissioned Jemison to create a custom painting from his family’s Christmas card.

Contemporary art from continental Africa is greatly represented in the Cain home, from unique Senegalese sculptures to abstract paintings from the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

“It’s very heavy, don’t try to lift it,” he joked.

In East Lansing, the Shona people’s art is represented in a dedicated gallery exhibit at Saper Galleries and Custom Framing, opened by Roy Saper 45 years ago. Saper champions the gallery’s ability to bring awareness through art from all over the world and from different ethnicities. A team of one, Saper makes the decisions on the exclusive inventory and, after hundreds of submission reviews over the course of any given year, accepts under 1%. He also attends international art expos to discover unique pieces.

The gallery holds serpentine stone sculptures created in Zimbabwe by the Shona people. An example includes “Dancing Family of 3,” by Francis Chikowore, a 13-inch-tall, hand-carved cobalt stone sculpture of three intertwined people. Saper said the Shona people value ukama, a term that represents the concept or state of togetherness and kinship.

“There’s nothing more precious than family, and the tribe expresses that,” he said.

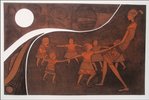

Saper also showed off a sculpture series of Black figures dressed in natural materials such as fur and beads made from coconuts. It was created by Loberto Hollanda, a Brazilian artist that aims to unite the country’s three identities (African, European and Indigenous). Lastly, he introduced Mathias Muleme, a Ugandan artist whose pieces he first purchased back in 1992. Currently, Muleme’s work at Saper Galleries includes the recently sold, “Ring Around 06,” an embossed etching of six children and an adult in motion underneath the sun, like the playground nursery rhyme “Ring Around the Rosie.”

At another Lansing gallery, the Michigan Institute for Contemporary Art in Old Town, Julian Van Dyke, a Black artist and author, is currently exhibiting some of his work alongside two other Lansing-based artists.

Originally from Benton Harbor, Van Dyke opened his studio in Old Town around 1999. He says the various forms of art in Lansing keeps his love of the craft alive. He also attributes his relationships with other artists as key to remaining active in Lansing.

“I think it’s very important that we know each other and obtain each other’s artwork. You know, artwork is a business,” he said.

Art doesn’t just have to be showcased in galleries or stately personal collections. At Western Michigan University’s Thomas M. Cooley Law School, a small offering of official lithographs (a printing style of oil-based materials and water on metal or stone, resembling paintings) and donated collections of music-related historical items are on display. James McGrath, president and dean, first showed off a lithograph of the iconic Norman Rockwell painting “The Problem We All Live With,” depicting Ruby Bridges being escorted by U.S. marshals into a recently desegregated New Orleans public school.

The school’s library holds another lithograph, “Crusaders for Justice,” by Elizabeth Catlett, a Black, modernist artist. The piece shows Thurgood Marshall, the first Black justice of the Supreme Court, behind two people, deep in research.

On another floor of the school, there are walls full of music posters, festival photos and old concert memorabilia featuring Black musicians, provided by Joseph Kimble, professor emeritus.

The statistics behind the underrepresentation of Black art in museums across the United States alone are staggering. After surveying and examining 31 museums in the U.S., a report published by Artnet News showed that exhibitions between 2008 and 2020 were made up of only 6.3% Black American art. More in-depth statistics reveal positive change, however — between 2008 and 2019, exhibitions of Black art increased by 235% and continued to increase in 2020.

These numbers are what makes Lansing’s art community unique, because not all museums are one-size-fits-all. Independent collectors can deliberately choose the art that speaks to them or represents their life experience, giving Black art a chance to shine.

“I think Black artists are finally getting the recognition of being shown, but at the same time, being bought and being collected, Van Dyke said. “That’s important too.”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here