It’s not Carlsbad Caverns, but it’s bad enough.

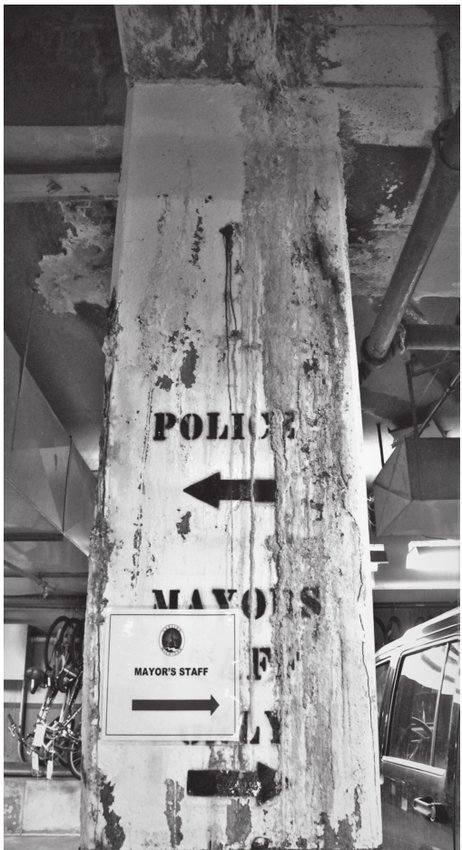

Stalactites of calcified minerals ooze down the walls and columns of the parking structure underneath Lansing City Hall. Plywood coffins float overhead, bolted to the ceiling to keep slabs of concrete from crushing cars.

Age is catching up with the glassy slab of mid-century modernism at the corner of Michigan and Capitol avenues.

City Hall was a sleek, forward-looking architectural gem when it was built in 1958, but now it’s the subject of a question whispered about a lot of Baby Boomers these days — what are we going to do with Grandpa?

The city wants to offload the aging equipment, drafty walls, crumbling plaza and other headaches and sell City Hall to a private developer with pockets deep enough to give the building a new life, perhaps as a hotel and restaurant overlooking the state Capitol.

If the plan works out, the mayor and other officials would leave their prime views for Lansing’s guests and tourists to enjoy, like good hosts, and move City Hall into a new spot, downsized to fit smaller payrolls of the 21st century, with centralized services and public parking.

Abstract and concrete

Lansing property manager Martin Riel is a building geek. He loves his job so much he tours other buildings while on vacation.

A few years ago, he met his counterpart at the Empire State Building.

“I wouldn’t want his job,” Riel said. Riel and his team have their hands full patching, caulking and duct taping City Hall together.

“This is a very unique building, and we’re trying hard to take care of it,” Riel said.

Last week, Riel, public service director Andy Kilpatrick and building services supervisor Laurie Stocker walked through the building, from basement to roof, to survey its condition.

Mayor Andy Schor joined us in the parking structure under the Michigan Avenue plaza, where a chunk of concrete recently fell onto a van. City Hall’s leaky plaza and the cavernous garage below are the most dramatic front in an accelerating war with entropy.

“The building has got some sizeable needs,” Schor said. “We were told when we came in that it needs a comprehensive $55 million worth of work, and that doesn’t even include the lockup, which also has significant issues.” He was referring to the city’s jail, housed with the Police Department in the limestone-fronted portion of City Hall on the east side of the plaza.

Workers continuously caulk the plaza above the garage in what Riel called “a perpetual battle.”

“Water comes in here, makes its way down and things are starting to fall apart above and below,” Kilpatrick said.

The plaza itself is one of many bold features in architect Kenneth Black’s dramatic design for City Hall.

Glassy grids of modernist urbanity were immortalized in the credit sequence to Alfred Hitchcock’s 1959 film “North by Northwest,” a riff on the geometry of Manhattan’s 650 Madison Ave. — a ringer for the south face of Black’s city hall in Lansing.

Susan Bandes, an art historian at MSU and expert on mid-century modern architecture, has championed saving City Hall in many writings and talks, including an August 2017 City Pulse column.

“Lansing City Hall was built in a modern style using the latest glass and steel construction because then-Mayor Ralph W. Crego wanted to project an image of the future, of the forward thinking city government,” Bandes wrote.

By comparison, the old City Hall looked like a medieval castle, with turrets and crenellations for pouring boiling oil on enemies.

Black’s design was a deliberate nod to famous International-style buildings in New York such as Lever House and the United Nations.

“For the time it was built, it was state of the art, more advanced than any other building in Lansing at the time,” Riel said.

The blue panels on the north face of the building are made of a fiberglass-wood composite that was cutting edge in the 1950s. Riel compared them to the fiberglass panels on a vintage Corvette. A lifetime later, they are faded and worn in blotches that compromise their clean geometry.

The windows don’t open because in the 1950s, the newly forged gods of HVAC were expected to attend to all human comforts. But they have screens anyway — hundreds of them. Each tinted screen slides in and out of place so windows can be cleaned without leaving streaks. The screens also help to break up direct sunlight.

The system was innovative for its time, but Riel said they cause “big time” problems with maintenance. Look harder and you begin to see screens that are off-center and others that don’t match.

“They haven’t made this style in 20 years, and they’re very hard to find,” he said.

Because the windows don’t open, workers have to hang from scaffolds suspended from cable-anchored roof supports — or they used to. Nowadays, no structural engineer will certify the rails as safe because of the age of the building, according to Kilpatrick. Booms and baskets are used now, but they are expensive. Repairs often wait until enough work is needed to fill a day or more.

Stairway to nowhere

Screens or no, City Hall’s entire window system would never pass muster now.

“You talk about an Energy Star building — we’re nowhere near it,” Schor said. “This building is very inefficient.”

It was that way when former Mayor David Hollister, now City Hall’s namesake, was in office in the early 2000s.

“Those windows are so flimsy, it’s so poorly insulated, I’d be sitting there as mayor with a heater under my desk to keep warm,” Hollister said.

The windows on the adjoining police building, perpendicular to City Hall, have a different feature-slash-bug. Unlike the City Hall windows, they open, but they swivel from the center, to aid in cleaning and what Riel called “quick egress.”

And it’s a caulking nightmare. “Every time rain comes out of the west, it leaks really bad,” Riel said.

“And that’s where it comes from most of the time,” Kilpatrick added.

The counterpart to City Hall’s outdoor plaza is its grand indoor lobby, an impressive space graced with red marble columns, Indiana limestone and terrazzo floor.

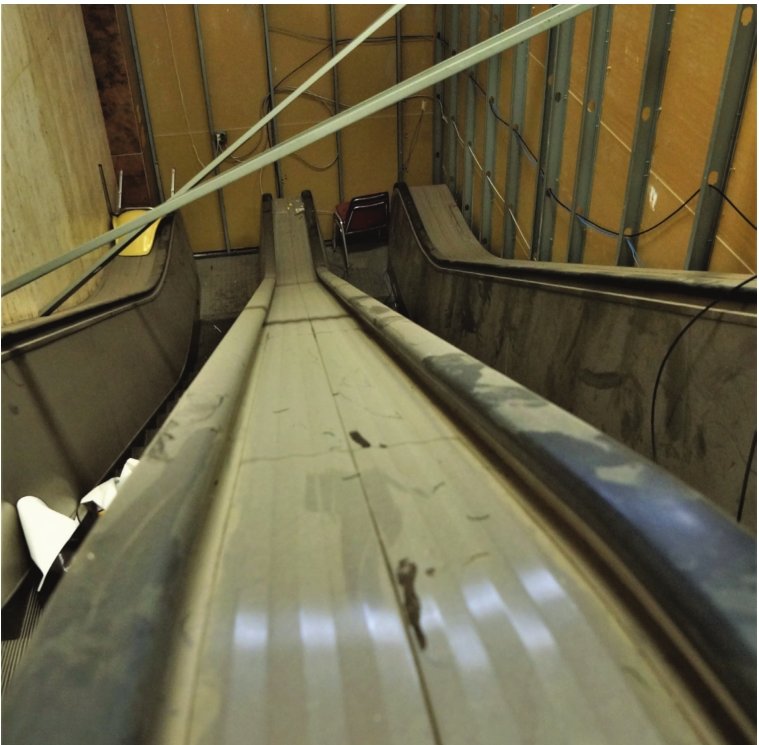

But the original design has been badly compromised. In 1958, a grand double staircase overlooking a fountain and an equally grand escalator, to the right of the staircase, ushered visitors up to the Ingham County Circuit Court, visible through a glass wall.

Construction of the state legislative offices next door, to the north, cut this space off like a giant meat cleaver.

Now the stairway leads to a blank white wall and a closed-off platform that houses old Christmas decorations. The long-dry fountain is capped by a plywood platform and the escalator is a dusty, inert anaconda of rubber and metal sequestered by white partitions because it would cost $80,000 to remove it.

Stocker pointed to the blank wall. The space between the city and state offices is still an odd little DMZ with fuzzy jurisdiction. A city-owned vault, now containing court records, is buried under the state’s side of the line.

“That’s our stuff, and that’s their stuff, and you sort of have this void in between,” Riel said.

“We still can’t turn off one bank of lights because the switch is on the other side,” Stocker said.

What do you do? “We leave them on.” Until they burn out? Then what? “Change the bulb.”

Towering inferno

Above City Hall’s ninth floor rests a vintage set of bulbous elevator cable housings, original to the building, where cables spin at high speeds.

Parts for the elevator guts, including the housings, haven’t been fabricated in decades.

“We’re cannibalizing them from other people that are replacing theirs,” Riel said. “It’s to the point where we’re going to have to start shutting down elevators because we can’t get parts for them anymore.”

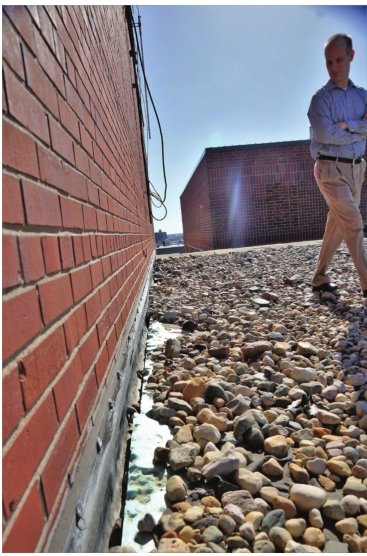

Stepping onto the roof, Schor and the party gawked at the Capitol dome, as one must, and then bent over to scrutinize the rubber membrane and loose stones that channel water on top of City Hall.

Kilpatrick declared the membrane “shot.” Several hulking hand-me-downs service City Hall, including a galvanized metal rooftop cooling tower moved in 1997 from the Ingham County jail, when the jail got a new one. (The previous one was made of wood.) In the electrical room sits a heavy 1950s-era generator cadged from Fire Station No. 1 when the fire station got an upgrade.

All of these units are reaching the end of their useful life.

In the service floor on top of the building, thin piping for pneumatic HVAC controls — fascinating to look at but antiquated — forms a web going in all directions.

(Modern controls are electronic.)

Nearby, a bank of steampunk-ish levers —modulating valves, or “mod motors” — control the flow of heated air and connect to thermostats in the offices. A water pump oozes calcifying water between layers of duct tape.

We ducked back into the ninth floor to witness the consequences of these slow failures as they creep into Council chambers and meeting room.

Riel and his crew have been fighting leaks here for years.

“We’ve tried several ways of doing it without replacing the entire roof,” Riel said.

In the hallways, horrid purple and pink 1970s-vintage wallpaper hides dry wall, which in turn hides the building’s original plaster. The plaster blistered several years ago from humidity and had to be covered up because “nobody fixes horsehair plaster anymore,” Riel said.

A small gray door in a restroom on the ninth floor opens, like Alice’s looking glass, into to another world — a giant vertical shaft running all the way up the building. The air duct in this shaft is wide enough for a horse to plummet freely. Huge pipe chases, or housings for all kinds of pipes, run up and down the walls.

We looked down through a series of gratings all the way down to the second floor.

Two floors below, we could see an empty pack of cigarettes that must have been left on top of a utility box years ago, in presmoke-free times.

Today’s tall buildings include masonry walls, door seals, dampers and other barriers to seal floors off from each other if a fire breaks out. This shaft does not include such safeguards. A shaft like this, Riel said, acts as a chimney in the event of fire.

“It’s called the towering inferno effect, and we don’t want that,” he said.

Moving the pieces

Schor, Kilpatrick and other city officials are eager to leave all these headaches to a private developer and turn City Hall into a money-making, tax-generating hotel complex.

“We’re getting there,” Schor said. “We need to move the pieces on the chessboard.”

In November, former Mayor Virg Bernero announced that the city had chosen a spiffy redesign by Beitler Real Estate of Chicago. The redesign would save City Hall by paying homage to Black’s design while bringing the building into the 21st century with LEED Silver certification and a green roof.

Schor likes the plan, but in March, he put a hold on any deal until space is found for the city lockup, where people are held for one to three days between arrest and arraignment, and 54A District Court offices.

“When we figure out these two pieces, then we can figure out where our departments are going to go, get out of the building and get it to a developer to make some money and get our people into a more workable environment,” Schor said.

Hollister is a big supporter of the plan to sell, even though his name is on the building.

“The value of that building as a highend, remodeled hotel, convention center, far exceeds what a patched-up City Hall would be,” Hollister said.

Both Hollister and Bernero have called the building “ugly,” but Schor is not that kind of a hater.

It’s not the debate over the aesthetics of mid-century modern design, and whether they are worth saving, that raises Schor’s temperature.

“We have people who park on the street and get a parking ticket because they are coming to a meeting with the mayor,” Schor said, visibly irritated. “People are trying to pay debts, take care of the issues they have with the justice system, and they’re getting parking tickets.”

To Schor, taking care of the parking problem, and setting up a one-stop payment center for city services, would send a more practical, powerful message that City Hall belongs to the citizens than planting a grand glass tower on a concrete plaza. That’s the kind of thing hotel moguls do better, and those guys pay taxes (or they should, anyway).

“If we spend $50-55 million to rehab this City Hall — we can make that happen,” Schor said. “Or we can spend that money — hopefully less — elsewhere, and use this place for economic growth. That’s the plan, but you have to move the chess pieces.”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here