Editor's Note: This story has been updated to clarify the views of Ingham County Commissioner Thomas Morgan on incentives for the Red Cedar development.

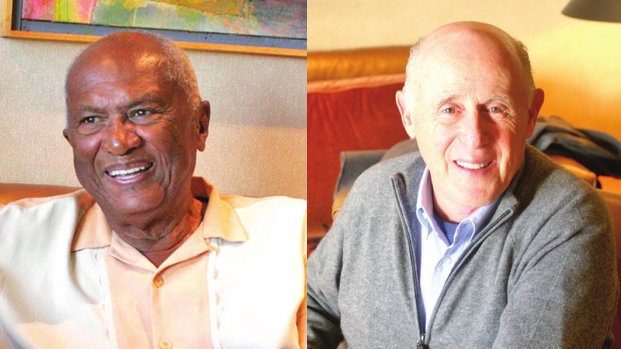

Joel Ferguson (left) and Frank Kass

A massive development project years in the making aims to reinvigorate an empty stretch of Michigan Avenue, connecting East Lansing to the capital city and spurring millions of dollars in economic growth for the region.

The redevelopment of the former Red Cedar Golf Course, once billed as the Red Cedar Renaissance Project, is garnering early support from the City Council. It would turn the abandoned golf course into a $250 million, mixed-use, super-development and create about 400 full-time jobs by the time it opens in 2023, officials said.

But before the project can get off the ground, it will take some clever financing plans that the Council must approve. Although developers call for nearly $200 million in private investment, they also aim to be reimbursed through more than $120 million in property taxes collected on the site over the next 30 years.

Some think the tax incentives have gone too far.

“I’m perplexed at the lack of scrutiny given to multi-million-dollar tax breaks for millionaire developers and corporations on these projects,” said Ingham County Commissioner Thomas Morgan. “The same folks that complain about these giveaways nationally generally stay silent or support the same practices on the local level.”

Proponents for the Red Cedar project — and others like it — argue that theoretical tax revenues requested for reimbursement wouldn’t exist but for the millions of dollars in private cash floating these ambitious projects. This particular deal also absolves the city of any financial exposure should the construction plans head south.

Critics, like Morgan, contended these types of projects could likely continue regardless of taxpayer support. As for the Red Cedar project specifically? This one "probably" could use the boost, Morgan added. But government officials should still tread cautiously when it comes to developer dependence on taxpayer cash, he emphasized.

Others suggested the return on these large-scale developments might not match the investment — largely mirroring a philosophical debate nation wide over tax incentives designed to spur development within urban areas much like the city of Lansing.

“As far as tax breaks for millionaires go, the Red Cedar project isn’t the most offensive plan around,” Morgan added. “As a city, we need to do this to compete for business. I get that. It still just doesn’t sit right with me that we continue to give our wealthiest citizens more and more tax breaks. The deal really shouldn’t be oversold.”

‘A game changer for Lansing’

The Red Cedar project, under its most recent iteration, would allow developers Frank Kass and Joel Ferguson to recoup costs of the initial sitework with decades of savings on future property taxes. They aim to use privately backed bonds sold by the city of Lansing to cover about $54 million in sitework, eventually repaid with interest by more than $120 million in taxes.

Ferguson heads up Ferguson Development in Old Town and serves as a trustee at Michigan State University. Kass chairs Continental Real Estate Companies, in Columbus, Ohio. Together, they agreed to buy the Red Cedar property from the city last July for $2.2 million.

Ferguson billed the development as a “game changer for Lansing” at a press conference on the project last week. It aims to connect the region’s busiest cities to MSU, clean up contamination, put the property back on the tax rolls and drive up tax revenues in the surrounding region. Lansing can’t afford to turn it down, some suggested.

“This property has sat there forever and it wasn’t going to be developed,” explained Bob Trezise, CEO of the Lansing Economic Area Partnership. “In almost all urban areas, there are going to be incentives involved with development. It’s not easy to launch into these sorts of projects.”

“I’d argue that this won’t cost the taxpayer a single penny. The only way it would actually cost them money is if we didn’t do this project. If it remains vacant, and Michigan Avenue continues to have this gigantic gap between Michigan State University, we’ll actually lose money that we could be taking into the city of Lansing.”

Because the 60-acre site is situated in the midst of a flood plain, significant groundwork is needed before construction can begin on a combination of market-rate and student housing, a dual-brand hotel, a parking structure, a senior care facility, an amphitheater and various mixed-retail spaces and restaurants weaved inside.

“It’s a great location, but it’s a terrible site,” contended project manager Christopher Stralkowski.

The City Council will review a Brownfield plan that uses tax-increment financing to cover the costs of environmental clean-up and infrastructure improvements at the site.

Decades of golf course maintenance (and the chemicals that come with it) have left the Red Cedar in pretty bad shape, according to the proposed plan.

Once its repaid with interest, the total property tax collection is estimated to rise as high as $123 million through 2050, according to the proposed plan. And because revenues used to repay the developers might not exist without the project, city leaders — like Mayor Andy Schor — have largely painted the deal as a win-win for the city and its taxpayers.

“The reality is, if we didn’t provide that tax incentive, there would be no project,” Schor contended.

‘A sweetheart deal’

Critics of the Red Cedar project — and others that capture eventual tax revenues to reimburse developers — argued a continued reliance on taxpayer support to drive development could be misguided. And those dollars could otherwise be used to support local services should they not be diverted away from the city, they said.

It’s the same philosophy that helped kill the deal with Amazon in New York. The company pitched a $30 billion return on nearly $3 billion in subsidies that were offered on the massive development. Still, critics argued the successful tech giant could afford to bear its own costs and could have been overselling its benefits to the city.

The pressure to limit developmental incentives, particularly to millionaire developers, has turned into a national dialogue that — in many ways — has played itself out in Lansing dozens of times over. The argument: If the development is such a “game changer” for the city, developers shouldn’t need to rely on any tax reimbursements.

“If it’s such a miracle project and it’s so important for the city, why can’t these developers put up their own money? At the end of the day, if this is successful, there will be millions made on this property each year,” said TJ Bucholz, CEO of Vanguard Public Affairs. “I see this as a real sweetheart deal for these developers.”

Bucholz serves as the spokesman for No Secret Lansing Deals — a “watchdog” group, as he describes it — that “works against developers that want to take money out of taxpayer pockets.” The group has long criticized Ferguson and his project, but Bucholz maintained he doesn’t receive any payment for his continued advocacy.

Schor also recently appointed Bucholz as a business owner member to the board at Downtown Lansing Inc.

“I’m under no illusion that we do need to do something with this property,” Bucholz added. “It needs to be developed. But in terms of the financial mechanisms used to reimburse the developers? It’s fuzzy math. It shows me the public is on the hook for at least a portion of this project. It’s coming from the city one way or another.”

Proponents recognize those concerns, but they still maintain the tax deal is necessary to spur development at a site that has been left to wither on the developmental vine for decades. And besides, without the project, there wouldn’t be any tax revenues to collect. It makes sense to give some back to development team, Stralkowski said.

Rendering of Red Cedar Project.

“There is no money,” Stralkowski added. “You don’t cut your way to growth. You spend and invest. You grow your community. You increase your tax base. If you shrink your tax base — in that you don’t have development along Michigan Avenue — you aren’t investing. Your tax base shrinks. Fewer services. Less quality of life.”

“You can’t realize these tax revenues until an investment is made.”

And without the project, the promises of its role as an economic driver for the region would be dashed. About $200 million that would have otherwise been infused into the community would never be spent. The River Trail wouldn’t connect to a walkway to MSU. Lansing would be left without its long-awaited gateway development.

No tax incentives, no project

Whether municipalities like Lansing are doing too much to incentivize development? It’s unclear. It takes an understanding of the financial mechanisms that makes these projects possible, and the answer depends on an overarching political ideology behind public taxpayer dollars heading to a private developers to churn a profit.

But Kass flipped the narrative: Could local governments be doing more to spur growth in their urban corridors?

“We’re not getting a tax incentive,” Kass explained in a recent interview with City Pulse. “We’re using future tax dollars. A tax incentive is an abatement. If the developer paid those costs independently, you could not do the project.

It wouldn’t happen. No one would stay there. It wouldn’t be priced according to the marketplace.”

When former Gov. Rick Snyder introduced a 6-percent corporate income tax rate in 2011, Michigan also began the process of reeling back its economic development incentives for large-scale projects like the Red Cedar. And Kass said Lansing — and Michigan — is “backwards” in terms of properly incentivizing new development.

He said a project like this in Ohio would have been welcomed with a sizeable tax abatement and larger financial benefits for his company that are simply unavailable in Michigan. Still, the project’s close proximity to MSU and East Lansing makes it worth his time to pursue construction in a “podunk” city like Lansing, he explained. Merriam Webster defines podunk as “a small, unimportant and isolated town.”

Kass — in a recorded interview with City Pulse — later tried to put his “podunk” comment off the record. City Pulse declined but did allow for his subsequent clarification. He emphasized that he simply meant Lansing was a smaller city with less financial tools than other metropolitans.

“If you can’t find a way to use future tax dollars to pay for infrastructure, there is no project,” Kass added. “If you build in Columbus, you get a 100-percent tax abatement for 15 years and zip none in Lansing. You guys are so backwards in terms of incentives the state allows you to have. Everybody knows that. The mayor knows that.”

Schor called Kass to discuss his recent comments on Monday after City Pulse sought reaction from members of the City Council. He said Kass must have gotten “a little bit emotional” and “said some things that he doesn’t mean.” He too recognizes that Michigan is comparatively limited on development incentives but stressed the deal is a fair shake for both parties.

Trezise has a more concise response to the suggestion that Kass could have still got a better deal: “That’s bullshit.”

Added Schor: “The city is offering exactly what it needs to bring this project in.”

Should the City Council approve the Brownfield plan, the Red Cedar project is slated to begin construction in 2020. At the same time, Ingham County Drain Commissioner Pat Lindemann is working to revamp the drain at surrounding the site and create a publicly accessible park area that’s planned to be weaved into the development.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here