Jeffrey Hank in front of one of his closed dispensaries.

An ordinance that enables Lansing to cultivate its medical marijuana market took effect one year ago this week, but the number of dispensaries within the city limits has only shrunk while other cities have been able to blossom.

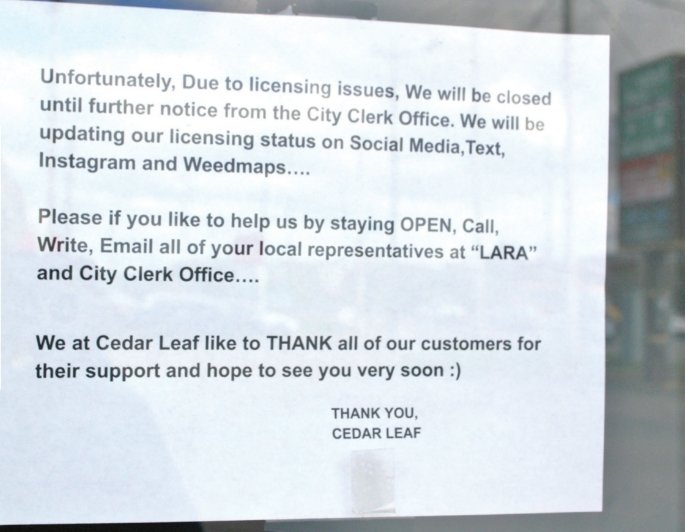

Lansing — as of Tuesday — has yet to provide a single operating license to any medical marijuana provisioning centers, forcing many longstanding businesses to shutter while only a handful have been temporarily able to remain in business. Meanwhile, other cities like Ann Arbor, have showered their shops with dozens of licenses.

Some contended Lansing, comparatively, has only squandered an economic opportunity. So, what gives? Is Lansing as welcoming to medical marijuana as its ordinance would suggest? What’s causing these delays? And exactly how many dispensaries are still able to provide their medicine to the thousands of patients regionwide?

More than 60 dispensaries — some estimated more than 80 — lined Lansing streets last October before the industry was wrapped into a contentious regulatory structure designed to cherry-pick the creme of the marijuana crop. But one year later, the city is home to fewer than 10 dispensaries — the final holdouts in an industry vexed with frequent uncertainties.

The city received 85 applications for dispensaries by the Dec. 15 deadline last year.

Just 27 remain pending. The rest were rejected or withdrawn. (Businesses that did not apply were forced to close for that reason.)

Of those 27 pending applications, how many applicants are actually operating? City Clerk Chris Swope’s office couldn’t be sure. So, City Pulse conducted its own survey by going to every address on the pending applications.

It found nine in business. They are listed on page 9.

Lansing vs. Ann Arbor

“It’s just frustratingly slow,” said Jeffrey Hank, whose name is listed on eight local, medical marijuana-related license applications. “You have a state bureaucracy and a local bureaucracy standing in the way of this industry really taking off. Lansing was a leader at one point, and we’ve kind of lost that momentum.”

Hank, an attorney in Lansing, has been involved in the local marijuana movement for a decade. Three of his applications are for provisioning centers, two of which are tied up in an appeal after Swope rejected their applications. The third is pending a decision. One of his partners also used to operate Best Buds, repeatedly voted “Top of the Town” by City Pulse readers before it was forced to close.

“It’s widely recognized not to put all your eggs in the Lansing basket,” Hank added. “I have clients that want to get into this industry but they won’t even think about coming to this city, even for a growing operation, because the city has made this so much more difficult than it needs to be. And it seems most are too scared to speak up.”

Ann Arbor — which opted into its own marijuana ordinance more than a month after Lansing — has since been able to provide local approval to 24 provisioning centers. The local statute there caps the number at 28. But city officials said the results provide actual proof that their system is working as the market climbs to capacity.

“I don’t know if there’s a perfect solution, but what we’re doing seems to have worked,” said Ann Arbor City Planner Brett Lenart. “Frankly, with this market just opening up, communities have to decide for themselves an equitable way of making decisions. By making it that way, there’s going to inherently be some flaws out there.”

‘An inadequate system’

Dispensaries statewide require two sets of licenses before they can open up shop: One from the Michigan Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs and another from their respective municipality. And Lansing has so far relied on a point-based system to select the top-performing businesses based on a variety of criteria.

Swope, who maintains primary discretion over which shops receive an operational nod from the city, said he was forced to hire a full-time employee to sort through more than 100 applications. The city has also paid nearly $80,000 to an out-of-state consulting firm tasked with processing business plans for would-be dispensaries.

Some have argued the point-based system — with a heavy focus on job creation and capital investment — gives preferential treatment to outside investors with money to blow, while local shops are largely left to wither on the vine. A series of ongoing lawsuits have since been filed in protest of the city’s merit-based selection methodology.

Swope conceded that the selection proocess was much more “complex” than he ever imagined. But in large part, his office is only playing the cards it was dealt. The local ordinance specifically calls for a point-based system and doesn’t offer an opportunity for improvement to low-scoring businesses that didn’t make the cut.

“Lansing has just made this unnecessarily hard on itself and it’s a shame,” Hank added.

Details regarding denied license applications are also specifically exempt from disclosure under Michigan’s Freedom of Information Act, essentially making it impossible to determine why certain businesses were shot down in the regulatory structure while others prevailed. And most applicants, for context, are from out of town.

“City officials bought into this and are having trouble acknowledging the system is broken,” Hank said. “Those scorecards are completely screwed up. Everyone who has seen their scores knows this is an inadequate system. I’d imagine it’s hard for them to admit that they’ve created a crappy process that shuts down legitimate businesses.”

In Ann Arbor, by comparison, the early birds get the medical worms. Applicants need only a special land use exemption from the city’s Planning Commission and another, related zoning compliance permit. From there, City Clerk Jacqueline Beadry checks for compliance and essentially rubber stamps applicants for approval.

Ann Arbor also doesn’t score applications.

Beadry, accordingly, holds no discretion over who stays or leaves.

“The city clerk’s approval is largely contingent on land-use approvals,” Lenart explained. “In short, it’s first come, first served. When the standards were adopted, existing dispensaries that had operated in the city were provided an opportunity to submit for a special land use permit before it was opened to the general market.”

Lenart said he was hesitant to endorse a process that eventually led to groups of applicants literally camping out in front of City Hall, eager to get their applications in the city’s selection hopper. But the goal — which was achieved — was to ensure consistent medication availability both before and after the ordinance took effect.

When the general public was eventually invited to apply for licenses, Ann Arbor officials were overwhelmed with the number of applicants, Lenart said. Only then did its City Council decide to enact a 28-shop limit on the market. He said city officials have only been able to learn from perceived licensing failures within other cities.

“On the whole, yes, I think we’ve put a stake in the ground a little more quickly, perhaps, than other cities in the state,” Lenart added. “At the same time, I think a lot of different communities are still looking at this and, in the end, the industry will be a bit more balanced all across the state. It’ll take time to work out the kinks.”

Ongoing appeals have also bogged down the process in Lansing. Should the 25 appealing applicants find success in reversing the denial of their license, there needs to be space in the market to accommodate their business. A judge’s order ultimately prohibits Swope from issuing licenses until that appeals process has been completed.

“I think different communities are doing things differently, but this is the system that we have to deal with,” said Lansing Mayor Andy Schor. “We’re following the ordinance that’s on the books. We’re down the field with this ordinance that we passed a year ago and we contemplated it for a year before that. This is where we’ve landed.”

Ann Arbor, in contrast, has handled very few appeals to its land-use decisions. Dispensaries need to keep a set distance from one another, but the city’s selection system generally incentivizes entrepreneurs to meet those clearly defined zoning requirements before applications are ever submitted, according to city officials.

“Again, I don’t profess this process to to be perfect, but it has been effective,” Lenart added.

‘Working out the kinks’

Lansing’s Medical Marihuana Commission, an appointed, five-person, citizen committee tasked with reviewing licensing appeals, met last week to craft recommendations for the City Council. Chairwoman Tracy Winston said changes are needed to properly dole out licenses and ensure medication remains available for local residents.

And time is quickly running out. On Tuesday, LARA announced revised emergency rules guiding the industry for a fourth time, essentially allowing unlicensed facilities to remain in operation through the end of the month while officials wade through applications. Those who have been denied — regardless of their appeal — must cease operations by Oct. 31.

Any temporary operation after that date could be referred to the Michigan State Police, officials said.

And if Lansing cannot license dispensaries within the next few weeks, officials suggested the remaining nine provisioning centers would need to close. None of them can be approved by the state until Swope offers his approval. And at the moment, his hands are largely tied in the limited market by the ongoing appeals process.

“I think we have a chance to be on the map,” Winston said. “I think we have a chance to be a serious contender in the state. It’s just a matter of working out the kinks in the system. I know people are a little impatient, but I think that’s just where we’re at right now. I still hope to have that market potential in Lansing.”

The recommendations, finalized on Friday, ask the City Council to consider increasing the dispensary cap to a population-based one provisioning center for every 3,000 residents. Census records would peg that number at 38 — providing at least a 52 percent increase in the number of shops initially able to operate within city limits.

The commission is also looking for a workaround to the stalled appeals process. The recent recommendations suggest Council members should continue to expand the limit to allow every successful appeal to find a spot in the market. If approved, the 25-dispensary limit could ultimately climb as high as 57 provisioning centers.

Commissioners said they aren’t sure if their suggestions will find support on the City Council; they don’t really care.

Winston just wants to focus on identifying additional efficiencies to allow the top-performing applicants to continue business and to ensure patients have access to their medicinal bud long after the Oct. 31 deadline.

“It’s a new ordinance and not everything was thought out ahead of time,” Winston said. “It would be impossible to predict these things. You can’t account for everything and that, unfortunately, was one of the consequences of this ordinance. We made these recommendations because we know you can’t fool-proof everything.”

The recommendations also call for a review for clarity and consistency with state law and an amendment that would require entrepreneurs to make property improvements and to get involved with their local neighborhoods. “Beautification” and “positive impact” were important for the commission, Winston said.

‘Anything could happen’

Schor hadn’t seen the recommendations but suggested the city should first finish what it started before it attempts to navigate additional changes in an already fluid regulatory structure. He said Lansing — despite its decreasing number of dispensaries — has still maintained its position as a regional hub for medical marijuana.

“We’re going to finish the process and maybe look at some changes during this next round for five dispensaries,” Schor suggested, referring to the additional licenses that can be awarded in 2019.

“Anything could happen when the City Council goes into that ordinance. It could go backwards. There’s nothing to guarantee we’d ever see more dispensaries. There could be less. Who knows?”

And opposition certainly remains. Elaine Womboldt, the facilitator and founder of Rejuvenate South Lansing, was shocked to hear about the recommendation to expand the cap on dispensaries. She said any changes would fly in the face of democracy and noted she would vehemently oppose any additional dispensaries in the city.

“We don’t need enough provisioning centers to serve all of Michigan,” Womboldt said, complaining about the lingering weed smell and the people “hanging around outside” the existing shops. “Let the people in Dewitt figure this out. Let the people in Grand Ledge fight for this. All of these other cities aren’t on board with this.”

But advocates for change, like Denise Pollicello, the attorney who last month filed for the injunction against LARA’s emergency rules, have worked with medical marijuana entrepreneurs in cities all across Michigan, including Lansing. She said complaints like Womboldt’s are rooted in a “reefer madness” mentality.

She said the continued hesitation to treat medical marijuana dispensaries like any other business has contributed to a “slow rolling” of the industry. And many residents in local neighborhoods seem to panic uncecceasrily when they hear about a business that offers to sell marijuana around the block from their home, Pollicello added.

“I don’t think there was ever any intention to make this difficult,” Pollicello said. “That being said, Lansing was the first city to use this merit-based application system. And the first time I saw it, the very first thing I thought was lawsuit. This system is just a bunch of lawsuits waiting to happen.

“Cities need to treat these businesses like businesses and not like nuisances. That’s something the state has completely failed to do as well. They make it so difficult to start and run a marijuana-related business. There’s virtually no support from these municipalities. It’s really more like survival of the fittest out there.”

Lansing’s City Council will review the Medical Marihuana Commission’s recent recommendations later this month. Visit lansingcitypulse.com for previous and continued coverage on the medical marijuana industry.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here