If Brian Whitfield lives another 54 years, he will never have a problem recalling the summer of 2017. All he’ll have to do is bend over in his rocking chair at a precise 45-degree angle, and it will all come back to him.

Da-doom, da-doom, da-da-doom.

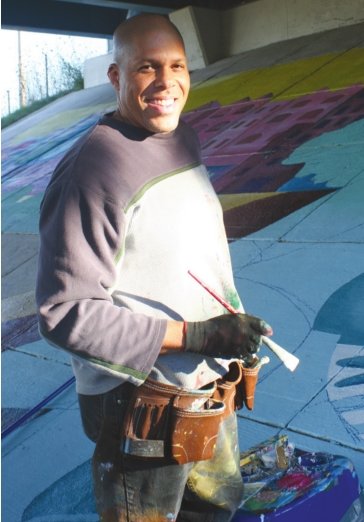

All summer, with thousands of cars and trucks chunking along on the I-127 overpass above his head, Whitfield has been hunched over the steep embankments along Michigan Avenue with a paintbrush in his hand.

Thanks to a warm October, four splendid murals, each one 50 feet wide and 25 feet tall, are almost finished. Suddenly, the dusty DMZ between Lansing and East Lansing is swirling with life and color — soft pastels in the morning shadows, aglow in colored lights at night.

Taken together, the murals unfold a sweeping panorama of Lansing area life. Two sun-splashed north panels are fragmented into the geometry of an auto assembly line to the east and a swooping, noodle-armed, one-on-one basketball match to the west, representing work and play by day.

The south panels are night scenes, with two exuberant teens chasing fireflies (and each other) to the west, and music festivals spilling into the streets to the east. The night panels are all about the joys of discovery — of nature, love, music and art.

Public art doesn’t have to be, and usually isn’t, this good. But Whitfield, a graphic artist who designed the state’s award-winning Mackinac Bridge license plate, is at the top of his game as a fine artist as well. A meticulous realist for many years, he is learning to loosen up, partly to get the massive project done on time.

“The bridge has been very liberating,” he said.

Bringing his fine arts training to the streets, Whitfield’s work fuses the monumentality of Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry murals with a bean-headed whimsy peculiar only to himself, with subtle shades of Cezanne and the wedges and curves of Russian master Wasilly Kandinsky deep in the mix.

Like most artists, Whitfield is his own harshest critic.

“It’s at a point where I’m OK with it,” he said after a day of hard work last Wednesday. “Today, I was out there, thinking, ‘It’s not as bad as I thought.’”

Fat Batman

Fat Batman

Try clambering up the Michigan Avenue embankment to take a closeup photo of the murals without falling backward, and your respect for Whitfield will double. God knows what hundreds of hours of concentrated stooping have been doing to his joints, bones and nerves.

“At first, I thought I wasn’t going to survive this mural,” he said. “My back was hurting, my legs were hurting, my ankles were killing me.”

His constant companions are a wagon of paint cans and supplies and a duct-taped plastic bucket, cut at a 45-degree angle so the paints stay level as he works.

“I couldn’t survive without that thing,” he said.

When he started work, he tried three different pairs of shoes, and none of them worked. The heels simply peeled off of a heavy pair of work boots. The human body was not built to tilt like this.

He found that three pairs of socks made it bearable.

“I got used to walking up and down the thing,” he said. “My feet don’t even hurt anymore.”

One night, after a day of bending in the same position with his hand on his knee, he went to a party where the music had a throbbing bass line. His whole left side started to vibrate, from his lip to his hand, arm, leg and foot.

“It was like an electric shock,” he said.

“I thought I was having a stroke.” The vibrations went on for about three weeks but subsided when he learned to shift his weight as he worked.

Quitting never occurred to him.

Whitfield has been creating art all his life and will probably keel over with a brush in his hand. His mother told him that as a baby, he bit bread into shapes and said things like “bird.”

“I can’t imagine not doing something artistic,” he said.

As a kid, he doodled superheroes and basketball players on pieces of cardboard his grandfather saved from dry cleaning. “But I put my own little spin on it,” he said. “I drew Batman or Spider-Man as children. A little fat, chubby Batman.”

Art classes at Pattengill Middle School, especially silkscreen printing and bookbinding, fascinated him.

He saw a silk-screen print of Earvin “Magic” Johnson, already a star at neighboring Everett High School, hanging in a showcase at school.

“For some reason, seeing that print pushed me to want to do it myself,” he said.

A late 1970s LP by Parliament/ Funkadelic, with a three-handed alien playing the keyboard, was the first album he ever bought. “I wasn’t even into the music,” he confessed.

He got encouragement from Larry Cross, his art teacher at Sexton High, and the art teacher across the hall, Mark Mehaffey, now a well-established Michigan artist.

In junior year, he took a three-hour commercial art class with an influential teacher, Lance Shade.

“He saw something in me,” Whitfield said. At Shade’s urging, Whitfield went to Kendall College of Art and Design. He got a day job in the mailroom at the state Department of Education, doing odd jobs likes logos and illustrations on the side.

In his spare time, he began studying old masters like Rembrandt and Da Vinci. He still loves the portraits he painted during this period: his mother, watering an ivy plant; his Aunt Hortense giving somebody the hairy eyeball; churchgoers receiving communion. The portraits are full of loving attention to folds in clothes, wrinkles in faces and necks.

Unlike many practitioners of cold photorealism, Whitfield’s portraits reveal a deeply empathic, loving eye.

In the late 1980s, Whitfield decided to commit to fine art and went back to school at the Maryland Institute College of Art. He was impressed that the dean was a strong African- American woman, Leslie King-Hammond. The feeling was mutual.

But Whitfield almost didn’t go. He was hesitant to leave his job and his girlfriend in Lansing.

“Get your butt here,” he recalled King- Hammond saying to him. “Don’t mess this up. We’ll find money for you.” She helped him get a Ford Fellowship that covered tuition.

Whitfield’s work as a graphic artist for Michigan’s Department of Transportation includes specialty signs like the “Cool Cities” signs seen around the state, “Lake Michigan Circle Tour” signs and other graphics.

In August 2013, Whitfield’s Mackinac Bridge state license plates were voted the world’s best by the Automobile License Plate Collectors Association, but police officers found that the numbers washed out when they aimed a flashlight at them.

Whitfield redesigned the plate, with black letters.

Along the way, Whitfield worked on several public murals in the area, but none of them had the scope and freedom of the bridge project.

Underpass ecosystems

Sprinkling fairy dust on a just-plain-dusty stretch of the Michigan Avenue corridor linking downtown Lansing to East Lansing and MSU has long been a goal for urban planners in the area. The Lansing Economic Area Partnership and the Michigan Economic Development Corporation led a broad alliance of business donors and arts groups to fund the project. A crowdfunding campaign raised $57,000, and MEDC matched it with $50,000.

Such overt “placemaking” art often skews toward the banal, but Whitfield was a perfect choice to give the project artistic heft and emotional investment.

“I’ve lived in different places and seen how Lansing is unusual — everybody seems to get along,” he said. “It’s a really diverse place in its thinking and actions. I wanted to show that Lansing was truly a great place to grow up.”

He is a proud member of a long-lived Lansing institution, the Earle Nelson Singers, a human bouquet of races, ethnicities and ages. Whitfield and his wife of nearly 25 years, Kimberly, live in Lansing, within walking distance of the overpass.

“Lansing’s not perfect, but looking around at other places, they’re really ahead of the game in a lot of ways,” he said. “People forget that because they’re here, and they don’t see it.”

Before starting work, Whitfield went to the Detroit Institute of Arts to study Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry murals. Two revered chroniclers of African- American life, collage artist Romare Bearden and painter Jacob Lawrence, were big influences as well.

The bridge project’s four-part scheme coalesced in his mind as he worked on preliminary sketches, beginning with the “work” and “play” sections to the north.

“GM makes Lansing different than anyplace in the world,” Whitfield said. “People work here, raise families. The kids are playing sports. You grow up in Lansing, you work, you have fun.”

In the southwest panel, “Discovery,” the kids grow to discover the world and each other. The “create” mural, to the northwest, centers on a jazz festival (both East Lansing and Lansing has one), with the Wharton Center in the background.

The musicians are not particular people.

“But that is Rodney Whitaker’s hat,” Whitfield said, referring to the world-renowned bassist and MSU Jazz Studies director. However, Whitfield deliberately made the bass player white, one of the basketball players female and one of the firefly chasers Asian, to keep the ball of inclusion unpredictable and aloft.

The panels are linked by countless little touches, such as the rays of sun spilling from the northwest to the northeast panel. Cameo appearances by several local landmarks, from MSU’s Beaumont Tower and Wharton Center to the state Capitol and the downtown Lansing Boji clock tower, help bind the four cityscapes into a larger vision.

Whitfield made sure that each of the panels doubles as a skillfully abstracted, energized composition — especially if you squint at them — but his realist skills came in handy, too. He thought about painting an assembly line out of his imagination, but he pictured GM workers driving by and shaking their heads in disapproval and did the research needed to get the machines right.

As the summer began, Whitfield planned on painting all day, but he got a quick education in underpass ecosystems on his first morning.

He found that roly-poly bugs swarmed over the concrete, beginning at about 11 a.m.

“You touch them and they’d roll down,” he said. “Then at about 12:30, the daddy longlegs come out, all over the mural. I don’t like spiders.”

He decided to begin work at one o’clock, when the bugs were gone.

The people he encountered during the day were a lot more congenial. Continuous encouragement from passers-by only confirmed the love of Lansing Whitfield was celebrating in paint.

“People yell at me all the time, but I haven’t heard one negative thing,” he said. “It’s all, ‘Good job, love it.’” Two weeks ago, a man walking by on the underpass gave him a $20 bill.

“Go get some art supplies,” the man said.

“I’ve got supplies.” “Just take it.” Later that day, the lanky, gap-toothed busker who plays guitar in the median of Michigan Avenue called it a day and was walking by. Whitfield slipped him the twenty.

In return, he was gratefully serenaded with “Smoke on the Water,” set to strumming chords, followed by a flurry of melodic finger picking. Whitfield captured the impromptu concert with his phone until he ran out of space.

“It’s too bad I didn’t get the part where he was picking,” Whitfield said. “He’s really good.”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here